The Life Stories of Eyewitnesses

The stories of the people who were imprisoned at Andreasstrasse during the SED dictatorship and those who opposed this dictatorship during the Peaceful Revolution make our Memorial and Educational Centre a site of living memory. A site where the history of dictatorship is presented in a new way, from the point of view of those affected, a site of exchange and discussion between the generations.

The life stories of our eyewitnesses make it clear how the SED dictatorship restricted the freedom and individual development of people in the GDR. But their stories also reveal the possibilities for self-assertion and the pockets of freedom GDR citizens carved out for themselves. Every life story is different and special. Each story awakens empathy and respect in its own way and reveals how important independent thinking and moral courage were then – and still are today.

The eyewitnesses and the associations they founded are a fundamental part of our daily remembrance work at the Andreasstrasse Memorial and Educational Centre — they are one of our most important sources of knowledge. We work closely with Freiheit e.V. (Freedom), the Vereinigung der Opfer des Stalinismus (VOS) e.V. (the Association of Victims of Stalinism) and the Gesellschaft für Zeitgeschichte e.V. (Society for Contemporary History).

In recent years, we have built up an extensive eyewitness archive consisting of personal documents, files, photos and video interviews. We have incorporated much of this information into our permanent exhibition “IMPRISONMENT | DICTATORSHIP | REVOLUTION”.

In addition, we are working on a complete overview of all people who were detained for political reasons in the prison at Andreasstrasse during the SED dictatorship. Such an overview already exists for the (to our knowledge) 5.523 prisoners who spent time in Stasi custody. This list was created together with the Stasi Records Archive, part of the German Federal Archives. For the political prisoners who were in the custody of the Volkspolizei (People’s Police) in the basement of the prison, such an overview does not yet exist.

Our Memorial and Educational Centre comes alive through the eyewitnesses and their life stories. It is important to us to share their stories with others and to learn from them. That is why we are grateful to all those who have biographical touch points with the ‘Andreasstrasse’ and would like to tell us their story.

If you are also an eyewitness, please do not hesitate to contact us. We always have an open ear and are there for you – even outside our opening hours and, if it is easier for you, outside the walls of the former prison.

Please contact:

Dr. Jochen Voit

voit@stiftung-ettersberg.de

T +49 (0)361 219212 – 12

M +49 (0)151 58754015

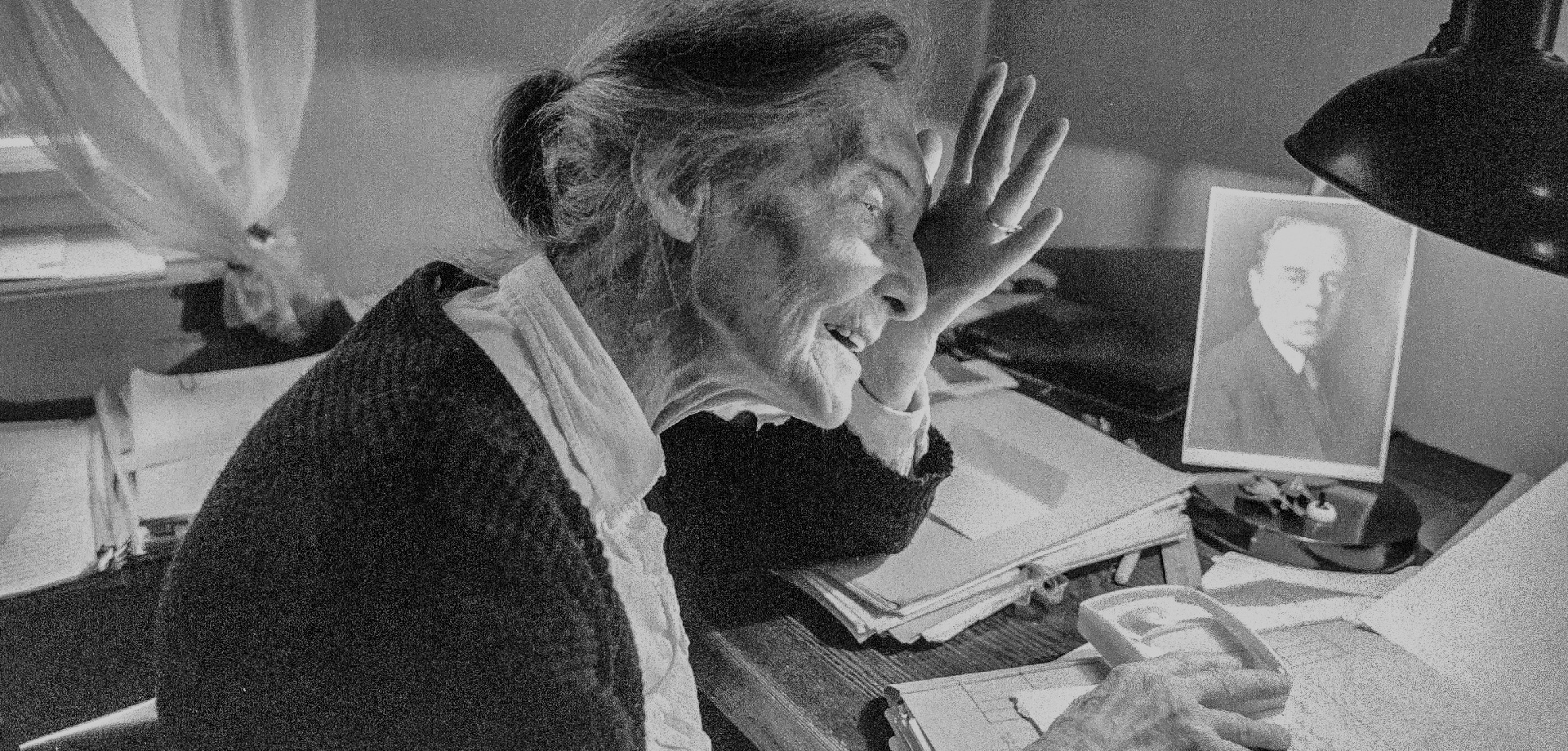

*1959 in Gotha

Accusation: ‘Incitement against the state’ according to §220 of the Criminal Code of the GDR,

detained in Andreasstrasse from June to December 1978

“My parents and the Church have always been my home and my support. In the Church, we had free spaces that did not exist in normal everyday life in the GDR. We didn’t lack for anything there. There were recreational opportunities, a youth choir, disco parties. In the Church, we could always openly say what we thought.”

Harald Ipolt and his three siblings grew up in a Christian family in the GDR. His parents keep him away from the mass organizations of the SED dictatorship. When Ipolt, aged 18, wanted to commemorate the popular uprising in the GDR on June 17, 1953, he went to prison for it. The sentence he wrote in chalk on a street in Gotha that became his undoing: “Long live the 17th of June.”

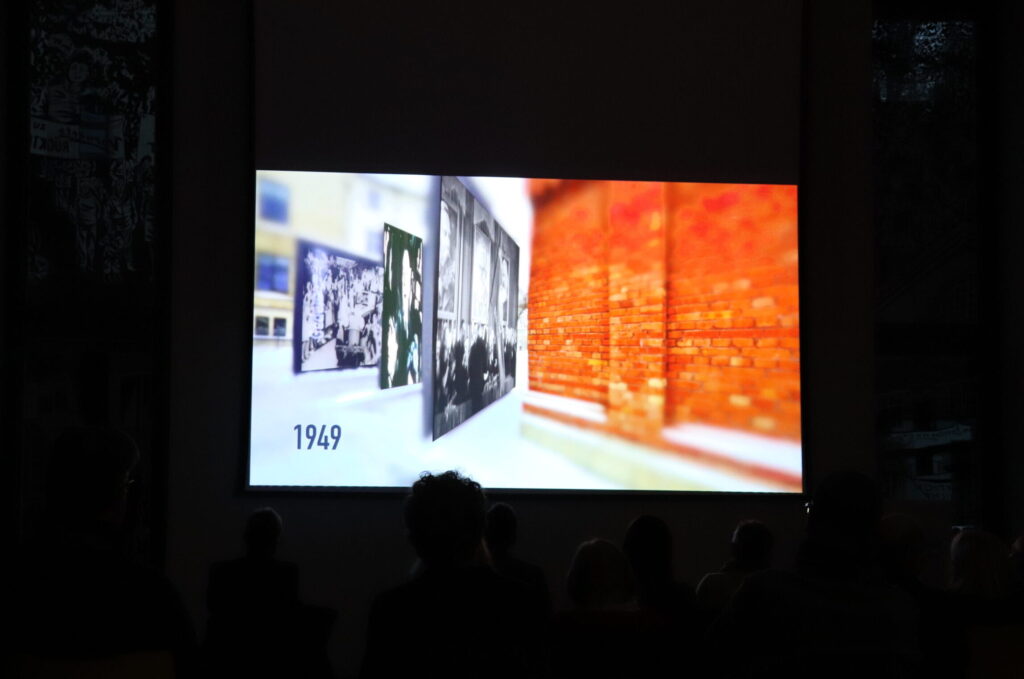

*1953 in Karl-Marx-Stadt, now Chemnitz

Dissident in the GDR and Participant in the 1989 Peaceful Revolution

“Gray, without prospects, imprisoned – and resistance. These are the things that come to mind when I think about the GDR today. At the end of the 1980s, there was a growing sense of dissatisfaction among the population. Via the magic of television, the whole of the GDR emigrated to the West every single evening. Other countries could not do that. Maybe that’s why, for us, it took so long for the revolution to arrive.”

From a very young age, Barbara Sengewald was critical of the GDR. She was already active in the Church and several opposition groups in the late 1970s. She knowingly risked her job at the municipal transport company in Erfurt, which she subsequently lost. As a single parent and without state support, she fought for herself, for her daughter, and for the freedom of the GDR.